- Home

- Lord Dunsany

Don Rodriguez; Chronicles of Shadow Valley

Don Rodriguez; Chronicles of Shadow Valley Read online

Produced by Robert Rowe, Charles Franks and the OnlineDistributed Proofreading Team. HTML version by Al Haines.

DON RODRIGUEZ

CHRONICLES OF SHADOW VALLEY

By

LORD DUNSANY

To WILLIAM BEEBE

CHRONOLOGY

After long and patient research I am still unable to give to the readerof these Chronicles the exact date of the times that they tell of. Wereit merely a matter of history there could be no doubts about theperiod; but where magic is concerned, to however slight an extent,there must always be some element of mystery, arising partly out ofignorance and partly from the compulsion of those oaths by which magicprotects its precincts from the tiptoe of curiosity.

Moreover, magic, even in small quantities, appears to affect time, muchas acids affect some metals, curiously changing its substance, untildates seem to melt into a mercurial form that renders them elusive evento the eye of the most watchful historian.

It is the magic appearing in Chronicles III and IV that has gravelyaffected the date, so that all I can tell the reader with certainty ofthe period is that it fell in the later years of the Golden Age inSpain.

CONTENTS

THE FIRST CHRONICLE HOW HE MET AND SAID FAREWELL TO MINE HOST OF THE DRAGON AND KNIGHT

THE SECOND CHRONICLE HOW HE HIRED A MEMORABLE SERVANT

THE THIRD CHRONICLE HOW HE CAME TO THE HOUSE OF WONDER

THE FOURTH CHRONICLE HOW HE CAME TO THE MOUNTAINS OF THE SUN

THE FIFTH CHRONICLE HOW HE RODE IN THE TWILIGHT AND SAW SERAFINA

THE SIXTH CHRONICLE HOW HE SANG TO HIS MANDOLIN AND WHAT CAME OF HIS SINGING

THE SEVENTH CHRONICLE HOW HE CAME TO SHADOW VALLEY

THE EIGHTH CHRONICLE HOW HE TRAVELLED FAR

THE NINTH CHRONICLE HOW HE WON A CASTLE IN SPAIN

THE TENTH CHRONICLE HOW HE CAME BACK TO LOWLIGHT

THE ELEVENTH CHRONICLE HOW HE TURNED TO GARDENING AND HIS SWORD RESTED

THE TWELFTH CHRONICLE THE BUILDING OF CASTLE RODRIGUEZ AND THE ENDING OF THESE CHRONICLES

DON RODRIGUEZ

THE FIRST CHRONICLE

HOW HE MET AND SAID FAREWELL TO MINE HOST OF THE DRAGON AND KNIGHT

Being convinced that his end was nearly come, and having lived long onearth (and all those years in Spain, in the golden time), the Lord ofthe Valleys of Arguento Harez, whose heights see not Valladolid, calledfor his eldest son. And so he addressed him when he was come to hischamber, dim with its strange red hangings and august with thesplendour of Spain: "O eldest son of mine, your younger brother beingdull and clever, on whom those traits that women love have not beenbestowed by God; and know my eldest son that here on earth, and forought I know Hereafter, but certainly here on earth, these women be thearbiters of all things; and how this be so God knoweth only, for theyare vain and variable, yet it is surely so: your younger brother thennot having been given those ways that women prize, and God knows whythey prize them for they are vain ways that I have in my mind and thatwon me the Valleys of Arguento Harez, from whose heights Angelico sworehe saw Valladolid once, and that won me moreover also ... but that islong ago and is all gone now ... ah well, well ... what was I saying?"And being reminded of his discourse, the old lord continued, saying,"For himself he will win nothing, and therefore I will leave him thesemy valleys, for not unlikely it was for some sin of mine that hisspirit was visited with dullness, as Holy Writ sets forth, the sins ofthe fathers being visited on the children; and thus I make him amends.But to you I leave my long, most flexible, ancient Castilian blade,which infidels dreaded if old songs be true. Merry and lithe it is, andits true temper singeth when it meets another blade as two friends singwhen met after many years. It is most subtle, nimble and exultant; andwhat it will not win for you in the wars, that shall be won for you byyour mandolin, for you have a way with it that goes well with the oldairs of Spain. And choose, my son, rather a moonlight night when yousing under those curved balconies that I knew, ah me, so well; forthere is much advantage in the moon. In the first place maidens see inthe light of the moon, especially in the Spring, more romance than youmight credit, for it adds for them a mystery to the darkness which thenight has not when it is merely black. And if any statue should gleamon the grass near by, or if the magnolia be in blossom, or even thenightingale singing, or if anything be beautiful in the night, in anyof these things also there is advantage; for a maiden will attribute toher lover all manner of things that are not his at all, but are onlyoutpourings from the hand of God. There is this advantage also in themoon, that, if interrupters come, the moonlight is better suited to theplay of a blade than the mere darkness of night; indeed but the merryplay of my sword in the moonlight was often a joy to see, it soflashed, so danced, so sparkled. In the moonlight also one makes nounworthy stroke, but hath scope for those fair passes that Sevastianitaught, which were long ago the wonder of Madrid."

The old lord paused, and breathed for a little space, as it weregathering breath for his last words to his son. He breatheddeliberately, then spoke again. "I leave you," he said, "well contentthat you have the two accomplishments, my son, that are most needful ina Christian man, skill with the sword and a way with the mandolin.There be other arts indeed among the heathen, for the world is wide andhath full many customs, but these two alone are needful." And then withthat grand manner that they had at that time in Spain, although hisstrength was failing, he gave to his eldest son his Castilian sword. Helay back then in the huge, carved, canopied bed; his eyes closed, thered silk curtains rustled, and there was no sound of his breathing. Butthe old lord's spirit, whatever journey it purposed, lingered yet inits ancient habitation, and his voice came again, but feebly now andrambling; he muttered awhile of gardens, such gardens no doubt as thehidalgos guarded in that fertile region of sunshine in the proudestperiod of Spain; he would have known no others. So for awhile hismemory seemed to stray, half blind among those perfumed earthlywonders; perhaps among these memories his spirit halted, and tarriedthose last few moments, mistaking those Spanish gardens, remembered bymoonlight in Spring, for the other end of his journey, the glades ofParadise. However it be, it tarried. These rambling memories ceased andsilence fell again, with scarcely the sound of breathing. Thengathering up his strength for the last time and looking at his son,"The sword to the wars," he said. "The mandolin to the balconies." Withthat he fell back dead.

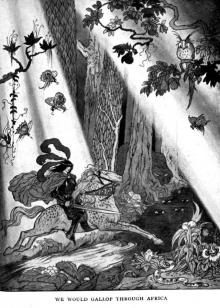

Now there were no wars at that time so far as was known in Spain, butthat old lord's eldest son, regarding those last words of his father asa commandment, determined then and there in that dim, vast chamber togird his legacy to him and seek for the wars, wherever the wars mightbe, so soon as the obsequies of the sepulture were ended. And of thoseobsequies I tell not here, for they are fully told in the Black Booksof Spain, and the deeds of that old lord's youth are told in the GoldenStories. The Book of Maidens mentions him, and again we read of him inGardens of Spain. I take my leave of him, happy, I trust, in Paradise,for he had himself the accomplishments that he held needful in aChristian, skill with the sword and a way with the mandolin; and ifthere be some harder, better way to salvation than to follow that whichwe believe to be good, then are we all damned. So he was buried, andhis eldest son fared forth with his legacy dangling from his girdle inits long, straight, lovely scabbard, blue velvet, with emeralds on it,fared forth on foot along a road of Spain. And though the road turnedleft and right and sometimes nearly ceased, as though to let the smallwild flowers grow, out of sheer good will such as some roads neverhave; though it ran west and east and sometimes south, yet in the mainit ran northward, though wandered is a better word than ran, and theLord of the Valleys of Arguento Harez who owned no valleys, or anythingbut a sword, kept company with it looking for the wars. Upon his backhe had slung his mandolin. Now the time of the year was Spring, notSpring as we know it in England, for it was but early March, but it wasthe time when Spring coming up out of Africa, or unknown lands to thesouth, first touches Spain, and multitudes of anemones come forth ather feet.

Thence she comes north to our islands, no less wonderful in our woodsthan in Andalusian valleys, fresh as a new song, fabulous as a rune,but a little pale through travel, so that our flowers do not quiteflare forth with all the myriad blaze of the flowers of Spain.

And all the way as he went the young man looked at the flame of thosesouthern flowers, flashing on either side of him all the way, as thoughthe rainbow had been broken in Heaven and its fragments fallen onSpain. All the way as he went he gazed at those flowers, the firstanemones of the year; and long after, whenever he sang to old airs ofSpain, he thought of Spain as it appeared that day in all the wonder ofSpring; the memory lent a beauty to his voice and a wistfulness to hiseyes that accorded not ill with the theme of the songs he sang, andwere more than once to melt proud hearts deemed cold. And so gazing hecame to a town that stood on a hill, before he was yet tired, though hehad done nigh twenty of those flowery miles of Spain; and since it wasevening and the light was fading away, he went to an inn and drew hissword in the twilight and knocked with the hilt of it on the oakendoor. The name of it was the Inn of the Dragon and Knight. A light waslit in one of the upper windows, the darkness seemed to deepen at thatmoment, a step was heard coming heavily down a stairway; and havingnamed the inn to you, gentle reader, it is time for me to name theyoung man also, the landless lord of the Valleys of Arguento Harez, asthe step comes slowly down the inner stairway, as the gloaming darkensover the fir

st house in which he has ever sought shelter so far fromhis father's valleys, as he stands upon the threshold of romance. Hewas named Rodriguez Trinidad Fernandez, Concepcion Henrique Maria; butwe shall briefly name him Rodriguez in this story; you and I, reader,will know whom we mean; there is no need therefore to give him his fullnames, unless I do it here and there to remind you.

The steps came thumping on down the inner stairway, different windowstook the light of the candle, and none other shone in the house; it wasclear that it was moving with the steps all down that echoing stairway.The sound of the steps ceased to reverberate upon the wood, and nowthey slowly moved over stone flags; Rodriguez now heard breathing, onebreath with every step, and at length the sound of bolts and chainsundone and the breathing now very close. The door was opened swiftly; aman with mean eyes, and expression devoted to evil, stood watching himfor an instant; then the door slammed to again, the bolts were heardgoing back again to their places, the steps and the breathing movedaway over the stone floor, and the inner stairway began again to echo.

"If the wars are here," said Rodriguez to himself and his sword, "good,and I sleep under the stars." And he listened in the street for thesound of war and, hearing none, continued his discourse. "But if I havenot come as yet to the wars I sleep beneath a roof."

For the second time therefore he drew his sword, and began to strikemethodically at the door, noting the grain in the wood and hittingwhere it was softest. Scarcely had he got a good strip of the oak tolook like coming away, when the steps once more descended the woodenstair and came lumbering over the stones; both the steps and thebreathing were quicker, for mine host of the Dragon and Knight washurrying to save his door.

When he heard the sound of the bolts and chains again Rodriguez ceasedto beat upon the door: once more it opened swiftly, and he saw minehost before him, eyeing him with those bad eyes; of too much girth, youmight have said, to be nimble, yet somehow suggesting to the swiftintuition of youth, as Rodriguez looked at him standing upon hisdoor-step, the spirit and shape of a spider, who despite her ungainlybuild is agile enough in her way.

Mine host said nothing; and Rodriguez, who seldom concerned himselfwith the past, holding that the future is all we can order the schemeof (and maybe even here he was wrong), made no mention of bolts or doorand merely demanded a bed for himself for the night.

Mine host rubbed his chin; he had neither beard nor moustache but worehideous whiskers; he rubbed it thoughtfully and looked at Rodriguez.Yes, he said, he could have a bed for the night. No more words he said,but turned and led the way; while Rodriguez, who could sing to themandolin, wasted none of his words on this discourteous object. Theyascended the short oak stairway down which mine host had come, thegreat timbers of which were gnawed by a myriad rats, and they went bypassages with the light of one candle into the interior of the inn,which went back farther from the street than the young man hadsupposed; indeed he perceived when they came to the great corridor atthe end of which was his appointed chamber, that here was no ordinaryinn, as it had appeared from outside, but that it penetrated into thefastness of some great family of former times which had fallen on evildays. The vast size of it, the noble design where the rats had sparedthe carving, what the moths had left of the tapestries, all testifiedto that; and, as for the evil days, they hung about the place, evidenteven by the light of one candle guttering with every draught that blewfrom the haunts of the rats, an inseparable heirloom for all whodisturbed those corridors.

And so they came to the chamber.

Mine host entered, bowed without grace in the doorway, and extended hisleft hand, pointing into the room. The draughts that blew from therat-holes in the wainscot, or the mere action of entering, beat downthe flame of the squat, guttering candle so that the chamber remaineddim for a moment, in spite of the candle, as would naturally be thecase. Yet the impression made upon Rodriguez was as of some olddarkness that had been long undisturbed and that yielded reluctantly tothat candle's intrusion, a darkness that properly became the place andwas a part of it and had long been so, in the face of which the candleappeared an ephemeral thing devoid of grace or dignity or tradition.And indeed there was room for darkness in that chamber, for the wallswent up and up into such an altitude that you could scarcely see theceiling, at which mine host's eyes glanced, and Rodriguez followed hislook.

He accepted his accommodation with a nod; as indeed he would haveaccepted any room in that inn, for the young are swift judges ofcharacter, and one who had accepted such a host was unlikely to findfault with rats or the profusion of giant cobwebs, dark with the dustof years, that added so much to the dimness of that sinister inn. Theyturned now and went back, in the wake of that guttering candle, tillthey came again to the humbler part of the building. Here mine host,pushing open a door of blackened oak, indicated his dining-chamber.There a long table stood, and on it parts of the head and hams of aboar; and at the far end of the table a plump and sturdy man was seatedin shirt-sleeves feasting himself on the boar's meat. He leaped up atonce from his chair as soon as his master entered, for he was theservant at the Dragon and Knight; mine host may have said much to himwith a flash of his eyes, but he said no more with his tongue than theone word, "Dog": he then bowed himself out, leaving Rodriguez to takethe only chair and to be waited upon by its recent possessor. Theboar's meat was cold and gnarled, another piece of meat stood on aplate on a shelf and a loaf of bread near by, but the rats had had mostof the bread: Rodriguez demanded what the meat was. "Unicorn's tongue,"said the servant, and Rodriguez bade him set the dish before him, andhe set to well content, though I fear the unicorn's tongue was onlyhorse: it was a credulous age, as all ages are. At the same time hepointed to a three-legged stool that he perceived in a corner of theroom, then to the table, then to the boar's meat, and lastly at theservant, who perceived that he was permitted to return to his feast, towhich he ran with alacrity. "Your name?" said Rodriguez as soon as bothwere eating. "Morano," replied the servant, though it must not besupposed that when answering Rodriguez he spoke as curtly as this; Imerely give the reader the gist of his answer, for he added Spanishwords that correspond in our depraved and decadent language of to-dayto such words as "top dog," "nut" and "boss," so that his speech had acertain grace about it in that far-away time in Spain.

I have said that Rodriguez seldom concerned himself with the past, butconsidered chiefly the future: it was of the future that he wasthinking now as he asked Morano this question:

"Why did my worthy and entirely excellent host shut his door in myface?"

"Did he so?" said Morano.

"He then bolted it and found it necessary to put the chains back,doubtless for some good reason."

"Yes," said Morano thoughtfully, and looking at Rodriguez, "and so hemight. He must have liked you."

Verily Rodriguez was just the young man to send out with a sword and amandolin into the wide world, for he had much shrewd sense. He neverpressed a point, but when something had been said that might mean muchhe preferred to store it, as it were, in his mind and pass on to otherthings, somewhat as one might kill game and pass on and kill more andbring it all home, while a savage would cook the first kill where itfell and eat it on the spot. Pardon me, reader, but at Morano's remarkyou may perhaps have exclaimed, "That is not the way to treat one youlike." Not so did Rodriguez. His attention passed on to notice Morano'srings which he wore in great profusion upon his little fingers; theywere gold and of exquisite work and had once held precious stones, aslarge gaps testified; in these days they would have been priceless, butin an age when workers only worked at arts that they understood, andthen worked for the joy of it, before the word artistic becameridiculous, exquisite work went without saying; and as the rings wereslender they were of little value. Rodriguez made no comment upon therings; it was enough for him to have noticed them. He merely noted thatthey were not ladies' rings, for no lady's ring would have fitted on toany one of those fingers: the rings therefore of gallants: and notgiven to Morano by their owners, for whoever wore precious stone neededa ring to wear it in, and rings did not wear out like hose, which agallant might give to a servant. Nor, thought he, had Morano stolenthem, for whoever stole them would keep them whole, or part with themwhole and get a better price. Besides Morano had an honest face, or aface at least that seemed honest in such an inn: and while thesethoughts were passing through his mind Morano spoke again: "Good hams,"said Morano. He had already eaten one and was starting upon the next.Perhaps he spoke out of gratitude for the honour and physical advantageof being permitted to sit there and eat those hams, perhapstentatively, to find out whether he might consume the second, perhapsmerely to start a conversation, being attracted by the honest looks ofRodriguez.

"You are hungry," said Rodriguez.

"Praise God I am always hungry," answered Morano. "If I were not hungryI should starve."

"Is it so?" said Rodriguez.

"You see," said Morano, "the manner of it is this: my master gives meno food, and it is only when I am hungry that I dare to rob him bybreaking in, as you saw me, upon his viands; were I not hungry I shouldnot dare to do so, and so ..." He made a sad and expressive movementwith both his hands suggestive of autumn leaves blown hence to die.

"He gives you no food?" said Rodriguez.

"It is the way of many men with their dog," said Morano. "They give himno food," and then he rubbed his hands cheerfully, "and yet the dogdoes not die."

"And he gives you no wages?" said Rodriguez.

"Just these rings."

Now Rodriguez had himself a ring upon his finger (as a gallant should),a slender piece of gold with four tiny angels holding a sapphire, andfor a moment he pictured the sapphire passing into the hands of minehost and the ring of gold and the four small angels being flung toMorano; the thought

darkened his gaiety for no longer than one of thosefleecy clouds in Spring shadows the fields of Spain.

Morano was also looking at the ring; he had followed the young man'sglance.

"Master," he said, "do you draw your sword of a night?"

"And you?" said Rodriguez.

"I have no sword," said Morano. "I am but as dog's meat that needs noguarding, but you whose meat is rare like the flesh of the unicorn needa sword to guard your meat. The unicorn has his horn always, and eventhen he sometimes sleeps."

"It is bad, you think, to sleep," Rodriguez said.

"For some it is very bad, master. They say they never take the unicornwaking. For me I am but dog's meat: when I have eaten hams I curl upand sleep; but then you see, master, I know I shall wake in themorning."

"Ah," said Rodriguez, "the morning's a pleasant time," and he leanedback comfortably in his chair. Morano took one shrewd look at him, andwas soon asleep upon his three-legged stool.

The door opened after a while and mine host appeared. "It is late," hesaid. Rodriguez smiled acquiescently and mine host withdrew, andpresently leaving Morano whom his master's voice had waked, to curl upon the floor in a corner, Rodriguez took the candle that lit the roomand passed once more through the passages of the inn and down the greatcorridor of the fastness of the family that had fallen on evil days,and so came to his chamber. I will not waste a multitude of words overthat chamber; if you have no picture of it in your mind already, myreader, you are reading an unskilled writer, and if in that picture itappear a wholesome room, tidy and well kept up, if it appear a place inwhich a stranger might sleep without some faint foreboding of disaster,then I am wasting your time, and will waste no more of it with bits of"descriptive writing" about that dim, high room, whose blacknesstowered before Rodriguez in the night. He entered and shut the door, asmany had done before him; but for all his youth he took some wiserprecautions than had they, perhaps, who closed that door before. Forfirst he drew his sword; then for some while he stood quite still nearthe door and listened to the rats; then he looked round the chamber andperceived only one door; then he looked at the heavy oak furniture,carved by some artist, gnawed by rats, and all blackened by time; thenswiftly opened the door of the largest cupboard and thrust his sword into see who might be inside, but the carved satyr's heads at the top ofthe cupboard eyed him silently and nothing moved. Then he noted thatthough there was no bolt on the door the furniture might be placedacross to make what in the wars is called a barricado, but the wiserthought came at once that this was too easily done, and that if thedanger that the dim room seemed gloomily to forebode were to come froma door so readily barricadoed, then those must have been simplegallants who parted so easily with the rings that adorned Morano's twolittle fingers. No, it was something more subtle than any attackthrough that door that brought his regular wages to Morano. Rodriguezlooked at the window, which let in the light of a moon that was gettinglow, for the curtains had years ago been eaten up by the moths; but thewindow was barred with iron bars that were not yet rusted away, andlooked out, thus guarded, over a sheer wall that even in the moonlightfell into blackness. Rodriguez then looked round for some hidden door,the sword all the while in his hand, and very soon he knew that roomfairly well, but not its secret, nor why those unknown gallants hadgiven up their rings.

It is much to know of an unknown danger that it really is unknown. Manyhave met their deaths through looking for danger from one particulardirection, whereas had they perceived that they were ignorant of itsdirection they would have been wise in their ignorance. Rodriguez hadthe great discretion to understand clearly that he did not know thedirection from which danger would come. He accepted this as his onlydiscovery about that portentous room which seemed to beckon to him withevery shadow and to sigh over him with every mournful draught, and towhisper to him unintelligible warnings with every rustle of tatteredsilk that hung about his bed. And as soon as he discovered that thiswas his only knowledge he began at once to make his preparations: hewas a right young man for the wars. He divested himself of his shoesand doublet and the light cloak that hung from his shoulder and castthe clothes on a chair. Over the back of the chair he slung his girdleand the scabbard hanging therefrom and placed his plumed hat so thatnone could see that his Castilian blade was not in its resting-place.And when the sombre chamber had the appearance of one having undressedin it before retiring Rodriguez turned his attention to the bed, whichhe noticed to be of great depth and softness. That something not unlikeblood had been spilt on the floor excited no wonder in Rodriguez; thatvast chamber was evidently, as I have said, in the fortress of somegreat family, against one of whose walls the humble inn had once leanedfor protection; the great family were gone: how they were goneRodriguez did not know, but it excited no wonder in him to see blood onthe boards: besides, two gallants may have disagreed; or one who lovednot dumb animals might have been killing rats. Blood did not disturbhim; but what amazed him, and would have surprised anyone who stood inthat ruinous room, was that there were clean new sheets on the bed. Hadyou seen the state of the furniture and the floor, O my reader, and thevastness of the old cobwebs and the black dust that they held, the deadspiders and huge dead flies, and the living generation of spidersdescending and ascending through the gloom, I say that you also wouldhave been surprised at the sight of those nice clean sheets. Rodrigueznoted the fact and continued his preparations. He took the bolster fromunderneath the pillow and laid it down the middle of the bed and putthe sheets back over it; then he stood back and looked at it, much as asculptor might stand back from his marble, then he returned to it andbent it a little in the middle, and after that he placed his mandolinon the pillow and nearly covered it with the sheet, but not quite, fora little of the curved dark-brown wood remained still to be seen. Itlooked wonderfully now like a sleeper in the bed, but Rodriguez was notsatisfied with his work until he had placed his kerchief and one of hisshoes where a shoulder ought to be; then he stood back once more andeyed it with satisfaction. Next he considered the light. He looked atthe light of the moon and remembered his father's advice, as the youngoften do, but considered that this was not the occasion for it, anddecided to leave the light of his candle instead, so that anyone whomight be familiar with the moonlight in that shadowy chamber shouldfind instead a less sinister light. He therefore dragged a table to thebedside, placed the candle upon it, and opened a treasured book that hebore in his doublet, and laid it on the bed near by, between the candleand his mandolin-headed sleeper; the name of the book was Notes in aCathedral and dealt with the confessions of a young girl, which theauthor claimed to have jotted down, while concealed behind a pillownear the Confessional, every Sunday for the entire period of Lent.Lastly he pulled a sheet a little loose from the bed, until a corner ofit lay on the floor; then he lay down on the boards, still keeping hissword in his hand, and by means of the sheet and some silk that hungfrom the bed, he concealed himself sufficient for his purpose, whichwas to see before he should be seen by any intruder that might enterthat chamber.

And if Rodriguez appear to have been unduly suspicious, it should beborne in mind not only that those empty rings needed much explanation,but that every house suggests to the stranger something; and thatwhereas one house seems to promise a welcome in front of cosy fires,another good fare, another joyous wine, this inn seemed to promisemurder; or so the young man's intuition said, and the young are wise totrust to their intuitions.

The reader will know, if he be one of us, who have been to the wars andslept in curious ways, that it is hard to sleep when sober upon afloor; it is not like the earth, or snow, or a feather bed; even rockcan be more accommodating; it is hard, unyielding and level, all nightunmistakable floor. Yet Rodriguez took no risk of falling asleep, so hesaid over to himself in his mind as much as he remembered of histreasured book, Notes in a Cathedral, which he always read to himselfbefore going to rest and now so sadly missed. It told how a lady whohad listened to a lover longer than her soul's safety could warrant, ashe played languorous music in the moonlight and sang soft by her lowbalcony, and how she being truly penitent, had gathered many roses, theemblems of love (as surely, she said at confession, all the worldknows), and when her lover came again by moonlight had cast them allfrom her from the balcony, showing that she had renounced love; and herlover had entirely misunderstood her. It told how she often tried toshow him this again, and all the misunderstandings are sweetly setforth and with true Christian penitence. Sometimes some little matterescaped Rodriguez's memory and then he longed to rise up and look athis dear book, yet he lay still where he was: and all the while helistened to the rats, and the rats went on gnawing and runningregularly, scared by nothing new; Rodriguez trusted as much to theirmyriad ears as to his own two. The great spiders descended out of suchheights that you could not see whence they came, and ascended againinto blackness; it was a chamber of prodigious height. Sometimes theshadow of a descending spider that had come close to the candle assumeda frightening size, but Rodriguez gave little thought to it; it was ofmurder he was thinking, not of shadows; still, in its way it wasominous, and reminded Rodriguez horribly of his host; but what of anomen, again, in a chamber full of omens. The place itself was ominous;spiders could scarce make it more so. The spider itself was big enough,he thought, to be impaled on his Castilian blade; indeed, he would havedone it but that he thought it wiser to stay where he was and watch.And then the spider found the candle too hot and climbed in a hurry allthe way to the ceiling, and his horrible shadow grew less and dwindledaway.

It was not that the rats were frightened: whatever it was that happenedhappened too quietly for that, but the volume of the sound of theirrunning had suddenly increased: it was not like fear among them, forthe running was no swifter, and it did not fade away; it was as thoughth

e sound of rats running, which had not been heard before, wassuddenly heard now. Rodriguez looked at the door, the door was shut. Ayoung Englishman would long ago have been afraid that he was making afuss over nothing and would have gone to sleep in the bed, and not seenwhat Rodriguez saw. He might have thought that hearing more rats all atonce was merely a fancy, and that everything was all right. Rodriguezsaw a rope coming slowly down from the ceiling, he quickly determinedwhether it was a rope or only the shadow of some huge spider's thread,and then he watched it and saw it come down right over his bed and stopwithin a few feet of it. Rodriguez looked up cautiously to see who hadsent him that strange addition to the portents that troubled thechamber, but the ceiling was too high and dim for him to perceiveanything but the rope coming down out of the darkness. Yet he surmisedthat the ceiling must have softly opened, without any sound at all, atthe moment that he heard the greater number of rats. He waited then tosee what the rope would do; and at first it hung as still as the greatfestoons dead spiders had made in the corners; then as he watched it itbegan to sway. He looked up into the dimness then to see who wasswaying the rope; and for a long time, as it seemed to him lyinggripping his Castilian sword on the floor he saw nothing clearly. Andthen he saw mine host coming down the rope, hand over hand quitenimbly, as though he lived by this business. In his right hand he helda poniard of exceptional length, yet he managed to clutch the rope andhold the poniard all the time with the same hand.

If there had been something hideous about the shadow of the spider thatcame down from that height the shadow of mine host was indeed demoniac.He too was like a spider, with his body at no time slender all bunchedup on the rope, and his shadow was six times his size: you could turnfrom the spider's shadow to the spider and see that it was for the mostpart a fancy of the candle half crazed by the draughts, but to turnfrom mine host's shadow to himself and to see his wicked eyes was tosay that the candle's wildest fears were true. So he climbed down hisrope holding his poniard upward. But when he came within perhaps tenfeet of the bed he pointed it downward and began to sway about. It willbe readily seen that by swaying his rope at a height mine host coulddrop on any part of the bed. Rodriguez as he watched him saw himscrutinise closely and continue to sway on his rope. He feared thatmine host was ill satisfied with the look of the mandolin and that hewould climb away again, well warned of his guest's astuteness, into theheights of the ceiling to devise some fearfuller scheme; but he wasonly looking for the shoulder. And then mine host dropped; poniardfirst, he went down with all his weight behind it and drove it throughthe bolster below where the shoulder should be, just where we slant ourarms across our bodies, when we lie asleep on our sides, leaving theribs exposed: and the soft bed received him. And the moment that minehost let go of his rope Rodriguez leaped to his feet. He saw Rodriguez,indeed their eyes met as he dropped through the air, but what couldmine host do? He was already committed to his stroke, and his poniardwas already deep in the mattress when the good Castilian blade passedthrough his ribs.

Fifty-One Tales

Fifty-One Tales Time and the Gods

Time and the Gods The Gods of Pegana

The Gods of Pegana A Dreamer's Tales

A Dreamer's Tales The Sword of Welleran and Other Stories

The Sword of Welleran and Other Stories Tales of Wonder

Tales of Wonder Tales of Three Hemispheres

Tales of Three Hemispheres The Book of Wonder

The Book of Wonder Gods, Men and Ghosts

Gods, Men and Ghosts The Curse of the Wise Woman

The Curse of the Wise Woman The Blessing of Pan

The Blessing of Pan In the Land of Time

In the Land of Time